Week 10: Juno and the Paycock (1930)

“Fellow countrymen, continuously and courageously we have fought and struggled for the national salvation of Ireland!”

“Fellow countrymen, continuously and courageously we have fought and struggled for the national salvation of Ireland!”

“‘Twas a darlin’ scramble, cap’n. A darlin’ scramble.”

“It’s miraculous. Whenever he senses a job in front of him, his legs begin to fail him.”

“Well, isn’t all religions curious? If they weren’t, how would you get anyone to believe in them?”

“He that goes a borrowin’, goes a sorrowin'”

“Here, get out o’ this! Ye’re nothin’ but a prognosticator and procrastinator!”

“What can God do agin’ the stupidity o’ man?”

–Juno and the Paycock

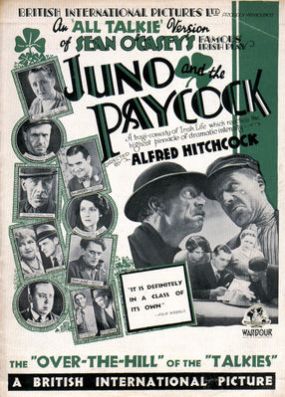

Alfred Hitchcock’s next project after Blackmail was an “all talkie” version of Irish playwright Sean O’Casey’s heavy social drama, Juno and the Paycock. As a sign of his growing fame and popularity, the director’s picture appears on promotional material alongside the rest of the cast. Hitch adapted the play himself, once again, and Alma (taking her first official screen credit since The Lodger) was responsible for the scenario. All talkie is certainly no exaggeration in this case. It contains few of the stylistic touches Hitchcock was best known for, and could have been the work of virtually any semi-competent director. As stage-to-film adaptations go, this one is exceptionally dry, perhaps one step above placing a static camera in front of a live production of the play. Hitchcock as director almost completely declines to breathe any cinematic life into the proceedings.

In fact, the production might be most notable for one of its least notable characters: the Orator that appears at the beginning, played by Barry Fitzgerald in his screen debut. Fitzgerald, best known for his lovable character work in such films as The Quiet Man, would go on to win an Oscar for his performance in 1944’s Going My Way. Another future Oscar nominee, Sara Allgood (How Green Was My Valley, 1941), plays Juno Boyle (of the title). She had previously appeared in Blackmail as Alice White’s mother. John Longden, also from Blackmail, appears here as Charles Bentham, a lawyer. Other actors include Edward Chapman as Captain Boyle, the strutting “paycock”(peacock) of the title, Sidney Morgan as Boyle’s no-good friend Joxer, and John Laurie and Kathleen O’Regan as Johnny and Mary Boyle, respectively.

In fact, the production might be most notable for one of its least notable characters: the Orator that appears at the beginning, played by Barry Fitzgerald in his screen debut. Fitzgerald, best known for his lovable character work in such films as The Quiet Man, would go on to win an Oscar for his performance in 1944’s Going My Way. Another future Oscar nominee, Sara Allgood (How Green Was My Valley, 1941), plays Juno Boyle (of the title). She had previously appeared in Blackmail as Alice White’s mother. John Longden, also from Blackmail, appears here as Charles Bentham, a lawyer. Other actors include Edward Chapman as Captain Boyle, the strutting “paycock”(peacock) of the title, Sidney Morgan as Boyle’s no-good friend Joxer, and John Laurie and Kathleen O’Regan as Johnny and Mary Boyle, respectively.

Most of the actors are competent, at least as far as can be judged through the thick brogue and sketchy early sound quality that heavily obscures the dialogue. Chapman, however, overacts unforgivably, perhaps a consequence of having only appeared on the stage previously (a handicap shared by most of the cast). His Captain Boyle is never much more than a shallow caricature, although he becomes far more subdued in the final scenes. Morgan, better known as a writer and director of silent pictures, does a far better job with Joxer, making the stereotype he plays seem far more natural, and even endearing. Best of all, though, is Laurie as the brooding, slightly-unhinged Johnny Boyle. His performance is subtle and affecting when it could have been merely broad and melodramatic.

Most of the actors are competent, at least as far as can be judged through the thick brogue and sketchy early sound quality that heavily obscures the dialogue. Chapman, however, overacts unforgivably, perhaps a consequence of having only appeared on the stage previously (a handicap shared by most of the cast). His Captain Boyle is never much more than a shallow caricature, although he becomes far more subdued in the final scenes. Morgan, better known as a writer and director of silent pictures, does a far better job with Joxer, making the stereotype he plays seem far more natural, and even endearing. Best of all, though, is Laurie as the brooding, slightly-unhinged Johnny Boyle. His performance is subtle and affecting when it could have been merely broad and melodramatic.

Juno and the Paycock is about the impoverished Boyle family living in Dublin during the Irish Civil War of the early 1920s. There’s the shiftless father who claims to have been a sea captain and gets awful pains in his legs when anyone offers him a chance at work and the hard-working, sharp-tongued mother (Juno). Then there’s son Johnny, who has lost his arm and acquired a permanent limp in some minor revolutionary skirmish on behalf of his country, and daughter Mary, a pretty girl who pulls her own weight and juggles a steady stream of beaus. The family experiences a windfall when a distant relative dies and leaves them a small fortune, and they waste no time in borrowing against the forthcoming inheritance to improve their quality of life.

Juno and the Paycock is about the impoverished Boyle family living in Dublin during the Irish Civil War of the early 1920s. There’s the shiftless father who claims to have been a sea captain and gets awful pains in his legs when anyone offers him a chance at work and the hard-working, sharp-tongued mother (Juno). Then there’s son Johnny, who has lost his arm and acquired a permanent limp in some minor revolutionary skirmish on behalf of his country, and daughter Mary, a pretty girl who pulls her own weight and juggles a steady stream of beaus. The family experiences a windfall when a distant relative dies and leaves them a small fortune, and they waste no time in borrowing against the forthcoming inheritance to improve their quality of life.

Tragedy strikes in droves, however, when the will proves to have been clumsily written, leaving them with next to nothing. Meanwhile, the lawyer who penned it knocks up poor Mary and absconds to England (leaving her unwed and in shame). Finally, the IRA discover that Johnny has ratted on a friend and haul him away to be executed as the local businessmen repossess everything the family owns. It’s pretty grim stuff, but then, I already said it was an Irish social drama.

Tragedy strikes in droves, however, when the will proves to have been clumsily written, leaving them with next to nothing. Meanwhile, the lawyer who penned it knocks up poor Mary and absconds to England (leaving her unwed and in shame). Finally, the IRA discover that Johnny has ratted on a friend and haul him away to be executed as the local businessmen repossess everything the family owns. It’s pretty grim stuff, but then, I already said it was an Irish social drama.

The film begins with the most (and perhaps only) imaginatively-filmed scene. The voice of Fitzgerald’s orator is heard just before he appears on the screen, delivering a rousing speech about the need for Irishmen to work together. As he speaks, the camera zooms back to reveal that he is standing in the

The film begins with the most (and perhaps only) imaginatively-filmed scene. The voice of Fitzgerald’s orator is heard just before he appears on the screen, delivering a rousing speech about the need for Irishmen to work together. As he speaks, the camera zooms back to reveal that he is standing in the middle of a small crowd on a Dublin street. As he talks, he holds a pipe in one hand and strikes a match in the other, but never lights up. Instead the match moves hypnotically back and forth as he talks, often threatening to ignite the pipe, but never quite making it (or going out). The camera shifts among some frighteningly-authentic looking close-ups of people in the crowd.

middle of a small crowd on a Dublin street. As he talks, he holds a pipe in one hand and strikes a match in the other, but never lights up. Instead the match moves hypnotically back and forth as he talks, often threatening to ignite the pipe, but never quite making it (or going out). The camera shifts among some frighteningly-authentic looking close-ups of people in the crowd.

Suddenly, with the speech in full swing, two men mount some sort of Gatling gun in an upper-story window and open fire indiscriminately on the crowd. Only the speaker seems to be hit, and the crowd scatters wildly, stampeding up the narrow street and ducking into doorways. One of these doorways

Suddenly, with the speech in full swing, two men mount some sort of Gatling gun in an upper-story window and open fire indiscriminately on the crowd. Only the speaker seems to be hit, and the crowd scatters wildly, stampeding up the narrow street and ducking into doorways. One of these doorways leads into a pub, where someone trips and the whole group ends up piled on the floor. Two men pick themselves up and dust themselves off with a surly dignity before stepping up to the bar to talk. These men are Captain Boyle and his friend Joxer, who are soon joined by Mrs. Madigan as they discuss the local goings-on. Chief among these is that the Republicans suspect the presence of an informer in the neighborhood.

leads into a pub, where someone trips and the whole group ends up piled on the floor. Two men pick themselves up and dust themselves off with a surly dignity before stepping up to the bar to talk. These men are Captain Boyle and his friend Joxer, who are soon joined by Mrs. Madigan as they discuss the local goings-on. Chief among these is that the Republicans suspect the presence of an informer in the neighborhood.

After an opening that included a crane shot, various quick cuts to distances ranging from medium to extreme close-up, and a chaotic stampede down the street, the film now settles into a much less fluid style. This scene, for instance, continues for some minutes without a single cut or camera movement. A few characters move in and out of the frame, but Boyle and Joxer remain centered and talking precisely where they are. Most of the film is shot in precisely this way, completely abandoning Hitchcock’s more familiar style of communicating visually by drawing our attention through carefully-selected camera movements and odd shooting angles.

After an opening that included a crane shot, various quick cuts to distances ranging from medium to extreme close-up, and a chaotic stampede down the street, the film now settles into a much less fluid style. This scene, for instance, continues for some minutes without a single cut or camera movement. A few characters move in and out of the frame, but Boyle and Joxer remain centered and talking precisely where they are. Most of the film is shot in precisely this way, completely abandoning Hitchcock’s more familiar style of communicating visually by drawing our attention through carefully-selected camera movements and odd shooting angles.

After Mrs. Madigan buys a round of drinks, Boyle and Joxer make their excuses and quickly duck out to avoid returning the favor. After Boyle assures Joxer that his wife is sure to be out, they head over to the Boyle lodgings: a ratty pair of rooms in a run-down tenement building. Juno is not out, as it happens, and Joxer leaves in a hurry while Juno lectures and nags her husband. Mary’s boyfriend shows up looking for her, and drops Boyle a tip on where he can pick up some work (much to his displeasure). He grumpily gets into his work clothes as Juno leaves for work.

After Mrs. Madigan buys a round of drinks, Boyle and Joxer make their excuses and quickly duck out to avoid returning the favor. After Boyle assures Joxer that his wife is sure to be out, they head over to the Boyle lodgings: a ratty pair of rooms in a run-down tenement building. Juno is not out, as it happens, and Joxer leaves in a hurry while Juno lectures and nags her husband. Mary’s boyfriend shows up looking for her, and drops Boyle a tip on where he can pick up some work (much to his displeasure). He grumpily gets into his work clothes as Juno leaves for work.

A few minutes later, however, she’s back, this time with Mary and a young lawyer named Charles Bentham in tow. Bentham relates the exciting news and the family rejoices at their new opportunities. The original play is done in three acts, a fact which becomes quite obvious here. Hitch only fades between acts, clearly delineating the passage of time and denoting the stage production’s need to drop the curtain and rearrange the set at those specific points. Except for the opening scene in and around the pub (the oration having been written specifically for the film), virtually everything happens inside the Boyles’ room. The staged nature of the whole production is emphasized by the fact that Hitchcock only films this room from one side, making it quite clear that this is merely a three-wall set.

A few minutes later, however, she’s back, this time with Mary and a young lawyer named Charles Bentham in tow. Bentham relates the exciting news and the family rejoices at their new opportunities. The original play is done in three acts, a fact which becomes quite obvious here. Hitch only fades between acts, clearly delineating the passage of time and denoting the stage production’s need to drop the curtain and rearrange the set at those specific points. Except for the opening scene in and around the pub (the oration having been written specifically for the film), virtually everything happens inside the Boyles’ room. The staged nature of the whole production is emphasized by the fact that Hitchcock only films this room from one side, making it quite clear that this is merely a three-wall set.

We now return to the more richly-furnished version of the Boyle lodging set-piece, where Bentham has become a regular visitor. Joxer and Mrs. Madigan appear as well, and the group throws a small party in celebration of the family’s good fortune. The eat, drink, laugh and sing along with the Boyles’ new phonograph. The proceedings are interrupted twice: First, by Johnny’s sudden panic in the next room when he believes he has seen a vision of his dead friend. Second, by the funeral for that friend, who lived upstairs from the Boyles with his mother. Juno and Mrs. Madigan attempt to comfort the old woman, but Boyle

We now return to the more richly-furnished version of the Boyle lodging set-piece, where Bentham has become a regular visitor. Joxer and Mrs. Madigan appear as well, and the group throws a small party in celebration of the family’s good fortune. The eat, drink, laugh and sing along with the Boyles’ new phonograph. The proceedings are interrupted twice: First, by Johnny’s sudden panic in the next room when he believes he has seen a vision of his dead friend. Second, by the funeral for that friend, who lived upstairs from the Boyles with his mother. Juno and Mrs. Madigan attempt to comfort the old woman, but Boyle quickly pulls them back into the celebration. Throughout this scene in particular, the shots often seem very poorly framed, cutting off the heads of the taller cast members in a most distracting fashion when there is no reason for the camera to be aimed so low. This could be the result of a poor DVD transfer, but if so it seems to be common to most of the existing versions of the film.

quickly pulls them back into the celebration. Throughout this scene in particular, the shots often seem very poorly framed, cutting off the heads of the taller cast members in a most distracting fashion when there is no reason for the camera to be aimed so low. This could be the result of a poor DVD transfer, but if so it seems to be common to most of the existing versions of the film.

Not long after this, Boyle learns that the money won’t be coming, but doesn’t say anything right away. Rumors begin to filter amongst the locals, and a tailor shows up to reclaim a new suit that Boyle has not yet paid for. Mrs. Madigan takes away the phonograph in payment for some cash that Boyle owes her. Soon after this, Juno returns with news of Mary’s pregnancy (a topic which the script completely avoids referring to directly, just as The Manxman sidestepped the same issue). Boyle rages, then tells her and Johnny the bad news about the money before leaving for the pub. Johnny is angry over Boyle’s desire to disown his daughter, but Juno restrains him.

Not long after this, Boyle learns that the money won’t be coming, but doesn’t say anything right away. Rumors begin to filter amongst the locals, and a tailor shows up to reclaim a new suit that Boyle has not yet paid for. Mrs. Madigan takes away the phonograph in payment for some cash that Boyle owes her. Soon after this, Juno returns with news of Mary’s pregnancy (a topic which the script completely avoids referring to directly, just as The Manxman sidestepped the same issue). Boyle rages, then tells her and Johnny the bad news about the money before leaving for the pub. Johnny is angry over Boyle’s desire to disown his daughter, but Juno restrains him.

Meanwhile, downstairs, Mary’s old boyfriend shows up and declares that he loves her and wants to marry her despite her indiscretions with Bentham. However, he was unaware that she is carrying the other man’s child, and quickly leaves after he finds out. As two men show up to remove all of the family’s possessions, Juno and Mary leave to see if Mary can stay with her aunt during “her trouble.” Two men in trench coats invade the room and escort a snivelling Johnny out at gunpoint.

A few hours later, Juno and Mary return and find their rooms almost completely cleaned out. News arrives through Mrs. Madigan that Johnny has been killed, and Juno sends Mary back to her aunt’s. She will join her there later, presumably without Boyle. Left alone in the empty room, Juno pours out her heart to the Virgin Mary statue mounted on the wall, wondering why they have deserved such tragedy and repenting of her earlier callousness towards her neighbor’s loss. She lifts her hands to heaven in supplication, then lets them fall dejectedly at her sides as the camera fades out for the last time.

A few hours later, Juno and Mary return and find their rooms almost completely cleaned out. News arrives through Mrs. Madigan that Johnny has been killed, and Juno sends Mary back to her aunt’s. She will join her there later, presumably without Boyle. Left alone in the empty room, Juno pours out her heart to the Virgin Mary statue mounted on the wall, wondering why they have deserved such tragedy and repenting of her earlier callousness towards her neighbor’s loss. She lifts her hands to heaven in supplication, then lets them fall dejectedly at her sides as the camera fades out for the last time.

In a 1963 interview, Hitchcock said of his involvment with the film, “[I]t was one of my favorite plays, so I thought I had to do it. It was just a photograph of a stage play.” This is, of course, correct, and the film suffers immeasureably as a result. However, it is worth noting that this is at least partially due to the constraints imposed on all early sound pictures, which Hitch had been able to work around a bit in Blackmail thanks to its being shot partially silent. The cameras in use at the time when talkies began were extremely loud and the noise they made was picked up by the microphones, so they had to be encased in suffocating sound-proof boxes which were not terribly mobile.

Furthermore, there was no process for mixing sound after, and all sound had to be recorded on the spot. Hitch noted in particular that the party scene, in addition to the actors, involved having a small orchestra, a prop-man to sing the song from the phonograph, a twenty-person choir for the funeral, and a sound-effect man all crowded uncomfortably into the studio. Even if the camera had been mobile (which it wasn’t) there was simply nowhere for it to go.

Like other heavy, socially-conscious fare of the 1930s and ’40s (i.e. How Green Was My Valley), Juno and the Paycock was well-liked when first released. The novelty of the talking picture was still fresh and the play and its message were popular and topical. Hitchcock himself felt keenly the failure to impart anything of his own to the work, believing any acclaim he received for the film to be largely misplaced. Over time, most have come to agree: this is a very minor piece of early Hitchcock. His talent was far better suited to entirely different sorts of endeavors.